Their life is mysterious, it is like a forest; from far off it seems a unity, it can be comprehended, described, but closer it begins to separate, to break into light and shadow, the density blinds one. Within there is no form, only prodigious detail that reaches everywhere: exotic sounds, spills of sunlight, foliage, fallen trees, small beasts that flee at the sound of a twig-snap, insects, silence, flowers.

And all of this, dependent, closely woven, all of it is deceiving. There are really two kinds of life. There is, as Viri says, the one people believe you are living, and there is the other. It is this other which causes the trouble, this other we long to see.

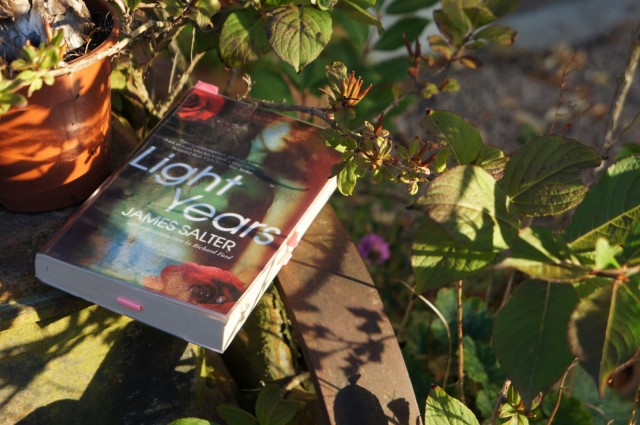

I’ve been seduced again. It started with William Maxwell a couple of years ago; then I fell headlong for Wallace Stegner; and now, now it’s James Salter. American men of almost the same generation. Maxwell and Stegner born within a year of each other in 1908 and 1909 respectively; Salter, the youngest of the three, born in 1925. What connects them in my mind — apart from the beauty of their writing — in The Château, Crossing to Safety and now Light Years, is their tender portrayal of marriage, their infinite sympathy for their characters, even at their least attractive. I couldn’t sleep last night, two maybe three weeks after I finished the book, for thinking about Nedra and Viri, and all that they had, and all that they wanted, and all that they lost. If you’re already feeling the seasons and years flitting by (say you have both a child starting school and a birthday next week) then this book might keep you awake too. But it’ll be worth it.

It all happens in an instant. It is all one long day, one endless afternoon, friends leave, we stand on the shore.

On the surface, Light Years is about Nedra and Viri, their marriage, their infidelities, their children, their friends, following them from their late 20s in 1958 when their daughters, Franca and Danny, are seven and five, to their late forties some twenty years later. Twenty years, but it feels both shorter and longer, as perhaps life does. Salter works through a kind of temporally-linear collage of memories: Christmas, days at the beach, birthday parties, dinner parties, conversations. Time unspools: a season is named and then another, and it takes a beat or two to realise that we’ve skipped ahead to another year. ‘She [Franca] is nine. Danny is seven. These years are endless, but they cannot be remembered.’ The organising principle, Salter says in his Paris Review interview, he later recognised in a Jean Renoir quote: ‘The only things that are important in life are the things you remember.’

The book is the worn stones of conjugal life. All that is beautiful, all that is plain, everything that nourishes or causes to wither. It goes on for years, decades, and in the end seems to have passed like things glimpsed from the train — a meadow here, a stand of trees, houses with lit windows in the dusk, darkened towns, stations flashing by — everything that is not written down disappears except for certain imperishable moments, people and scenes.

James Salter on his novel ‘Light Years’

Its a book built from the smallest of details and objects, from the flashes of life that endure. But, beneath the gilded surface of Nedra and Viri’s daily lives, desire, disillusionment and mortality pulse through Salter’s exquisite sentences. Their children grow and become adults themselves. They become older. Their desires, in the main, go unfulfilled. This makes it sound incredibly depressing; which it both is, and isn’t. It isn’t because writing this good could never be wholly depressing. And also because Nedra and Viri continually misjudge what will make them happy — possessions, money, travel, always a desire for change. Yes, life is short; but, knowing that, it is in our hands to choose carefully how to spend its limited days. Light Years is a beautiful reminder to do just that, even as I secretly long to live like Nedra.

Her [Nedra’s] life was like a single, well-spent hour. Its secret was her lack of remorse, of self-pity. She felt herself purified. The days were cut from a quarry that would never be emptied. Into them there came books, errands, the seashore, occasional pieces of mail. She read them slowly and carefully, sitting in the sunshine, as if they were newspapers from abroad.

******

There are two wonderful short essays on reading and re-reading Light Years on the Paris Review website by Jhumpa Lahiri — ‘As a writer, I am shamelessly in its debt.’ — and Porochista Khakpour. Already feeling haunted, I keep coming back these lines by Khakpour:

Nedra is as entirely unique and yet universal as any woman — at once hard and extravagant, both old and young, an artist and an observer, creator and destroyer, wanderer and homebody, a mother and the ultimate antimatriarch. Losing yourself in Nedra is dangerous; my experience — nearly a decade since I first read the book — is evidence enough that she can haunt you a few steps ahead of yourself.