The stories gets passed on and the truth gets passed over. As the sayin goes. Which I reckon some would take as meanin that the truth cant compete. But I dont believe that. I think that when the lies are all told and forgot the truth will be there yet. It dont move about from place to place and it dont change from time to time. You cant corrupt it any more than you can salt salt. You cant corrupt it because that’s what it is. It’s the thing you’re talkin about. I’ve heard it compared to the rock – maybe in the bible – and I wouldnt disagree with that. But it’ll be here even when the rock is gone.

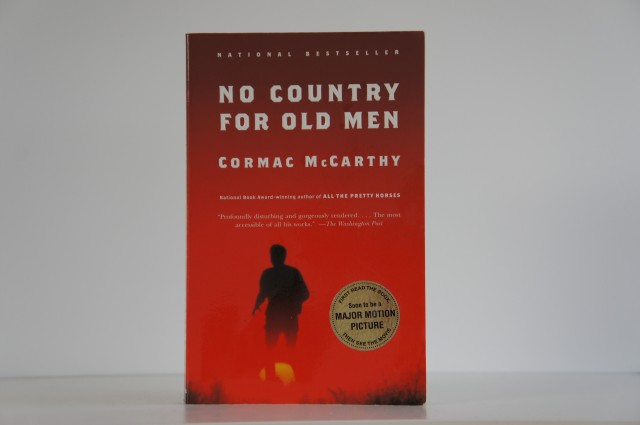

It isn’t often that I read a book because I saw the movie. But this is how it was with my first Cormac McCarthy novel. I read No Country For Old Men because I watched the film. And I only watched the film because I love the Coen brothers. (Yes, slightly late. The film came out in 2007. Who knew that in these years I’ve been busy having children they’ve remained busy making films?)

What to say about this book? That it is just like the film, only more so. That it is violent and terrifying and mesmerising. That it unfolds with the inevitability of Greek tragedy. That it evokes a world, the Texas-Mexico border in 1980, that is fallen, harsh and godless, with the good old boys, like Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, watching on unable to stop the escalating and apocalyptic violence.

Vietnam veteran and welder, Llewellyn Moss, is out hunting antelope when he finds a group of three vehicles surrounded by dead men. In the front seat of one of the trucks is a dying Mexican who begs him for water he doesn’t have; in the back of the truck is a load of heroin. Following a trail of blood – ‘You aint going far, he said. You may think you are. But you aint.’ – he finds one last body and a case stuffed full of banknotes. He takes the money. It’s not certain, but at this point things may still have gone another way. But Llewellyn too is one of the good old boys. That night, waking in his trailer beside his young wife, he is compelled to go back with some water for the half-dead Mexican. From this point on he is on the run from both Bell, who wants to save him, and from the chilling Chigurh. As Moss says to himself, ‘There is no description of a fool…that you fail to satisfy. Now you’re goin to die.‘

The language is spare and precise. The dialogue is brusque, fast-paced, often very funny despite everything. With the exception of Sheriff Bell, we only learn what the characters are thinking through what they say to one another or, occasionally, to themselves. Bell, whose italicized reminiscences start each chapter, seems a distant relation of Marilynn Robinson’s Reverend John Ames. A good man, old now and feeling passed by, ruminating on the past and what he believes. Yet Bell has none of Ames’ gentle optimism for the future. He believes in tending to those in his county as a minister would tend to his congregation. But he has no hope now for what’s ‘comin down the pike’: ‘Somewhere out there is a true and living prophet of destruction and I dont want to confront him. I know he’s real. I have seen his work. I walked in front of those eyes once. I wont do it again.’

It’s a book that took me to places I’ve never been, and places I would never want to. Out hunting with Moss, I felt the pleasure of following someone with deep knowledge of the landscape and the wildlife. I picked up new-to-me words like pebbles for my pocket: caldera and talus; bajada and rincon; winegrass and sacahuista. I saw how much can be done with so little exposition, how far dialogue and pared-down description can carry you. I’m left with the image of the world vanishing through the eyes of a dying man as his killer stands above him watching his own reflection disappear in those same eyes. Maybe, one day, I’ll be ready for The Road.

******

I knew practically nothing about Cormac McCarthy. When I’d finished No Country For Old Men and I wanted to find out more about the creator of this bleak vision, I discovered that he had – to me – a most unlikely friend: Nobel-prize winning physicist, Murray Gell-Mann. When I was doing A-level physics I was taught by two wonderful women. One of them handed round photocopies of a text book photograph of Gell-Mann. ‘He looks so kind,’ she said. ‘It will be nice for you to have him smiling at you from your notes.’ And so, for a while, he was my good luck talisman. A few years later, B & I went to see him speak at The Royal Geographical Society. He was every bit as lovely as he had looked. I think he talked about his Roman coin collection. By then I knew him as the discoverer of the fundamental particle, the quark. (Named for ‘a quark for Mister Mark’ in Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, but pronounced ‘quork’ by Gell-Mann, though all our lecturers said ‘quark’. Gell-Mann’s explanation is that he had the sound of the word in his head before he came across the line in Joyce which gave him the spelling.)

A final digression. In the descriptions of Moss hunting, McCarthy repeatedly uses ‘glassed’ as a verb for scanning with binoculars: ‘Moss…glassed the desert below him with a pair of twelve power german binoculars.’. It’s not a usage I’m familiar with, but I like it. Consulting the OED (the wonders of the internet & a library card!), I found glass as a verb, in this sense, as entry 4(c). The first quotation to support the usage? Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa (1935), ‘We glassed the country.’. I have a hunch that Cormac McCarthy already knew that.